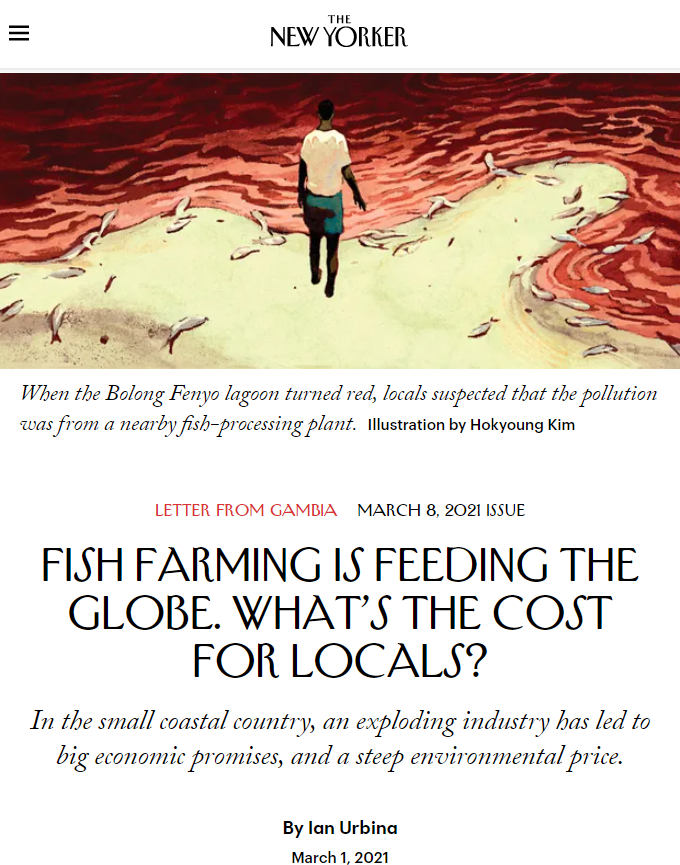

Í nýrri fréttaskýringu New Yorker er farið yfir hvernig dýrmætt prótein sem er dregið úr sjó við Afríku er flutt til annarra heimsálfa og Afríkubúar sitja eftir með sárt enni. Rányrkja er stunduð á fiskistofnum, mengun skilin eftir við strendur og lífsnauðsynleg næringarefni flutt burt.

Í nýrri fréttaskýringu New Yorker er farið yfir hvernig dýrmætt prótein sem er dregið úr sjó við Afríku er flutt til annarra heimsálfa og Afríkubúar sitja eftir með sárt enni. Rányrkja er stunduð á fiskistofnum, mengun skilin eftir við strendur og lífsnauðsynleg næringarefni flutt burt.

Gambía flytur úr meirihlutann af fiskimjöli sínu til Kína og Noregs, þar sem það knýr áfram framleiðslu á ofgnótt af ódýrum eldislaxi til neyslu í Evrópu og Bandaríkjunum. Á sama tíma er fiskurinn sem Gambíubúar byggja afkomu sína á að hverfa.

„Golden Lead (pronounced “leed”) is one outpost of an ambitious Chinese economic and geopolitical agenda known as the Belt and Road Initiative, which the Chinese government has said is meant to build good will abroad, boost economic coöperation, and provide otherwise inaccessible development opportunities to poorer nations. As part of the initiative, China has become the largest foreign financier of infrastructure development in Africa, cornering the market on most of the continent’s road, pipeline, power-plant, and port projects. In 2017, China cancelled fourteen million dollars in Gambian debt and invested thirty-three million to develop agriculture and fisheries, including Golden Lead and two other fish-processing plants along the fifty-mile Gambian coast. The residents of Gunjur were told that Golden Lead would bring jobs, a fish market, and a newly paved three-mile road through the heart of town.

Golden Lead and the other factories were rapidly built to meet exploding global demand for fish meal—a lucrative dark-yellow powder made by cooking and pulverizing fish. Exported to the United States, Europe, and Asia, fish meal is used as a protein-rich supplement in the booming industry of fish farming, or aquaculture. West Africa is among the world’s fastest-growing producers of it: more than fifty processing plants operate along the shores of Mauritania, Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, and Gambia. And the volume of fish they consume is enormous. One Gambian plant alone takes in more than seven thousand five hundred tons of fish a year, mostly of a local type of shad known as bonga—a silvery fish about ten inches long. …

Jojo Huang, the director of the plant, has publicly denied polluting nearby waters, and said that the facility follows all regulations for waste disposal. The plant has benefitted the town, Golden Lead told Reuters, by investing in local education and making Ramadan donations to the community. (The company did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Manjang, the microbiologist, was outraged by the plant’s apparent impunity. “It makes no sense!” he told me, when I visited him in Gunjur at his family compound, an enclosed three-acre plot with several simple brick houses and a garden of cassava, orange, and avocado trees. Behind Manjang’s thick-rimmed glasses, his gaze was gentle and direct, even as he spoke urgently about the perils facing Gambia’s environment. “The Chinese are exporting our bonga fish to feed it to their tilapia fish, which they’re shipping back here to Gambia to sell to us, more expensively—but only after it’s been pumped full of hormones and antibiotics,” he said. Adding to the absurdity, he noted, tilapia are herbivores that normally eat algae and other sea plants.“