„Troðið í sjókvíar í allt að tvö ár og aldir á verksmiðjuframleiddu fóðri, margir enda vanskapaðir, blindir, þaktir lús og éta jafnvel hvorn annan. Svo er það mengunin. Samkvæmt skosku umhverfisverndarstofnuninni streymir skordýraeitur frá 76 sjókvíaeldisstöðvum við landið úr kvíunum í slíku magni að það skaðar annað lífríki hafsins.“

„Troðið í sjókvíar í allt að tvö ár og aldir á verksmiðjuframleiddu fóðri, margir enda vanskapaðir, blindir, þaktir lús og éta jafnvel hvorn annan. Svo er það mengunin. Samkvæmt skosku umhverfisverndarstofnuninni streymir skordýraeitur frá 76 sjókvíaeldisstöðvum við landið úr kvíunum í slíku magni að það skaðar annað lífríki hafsins.“

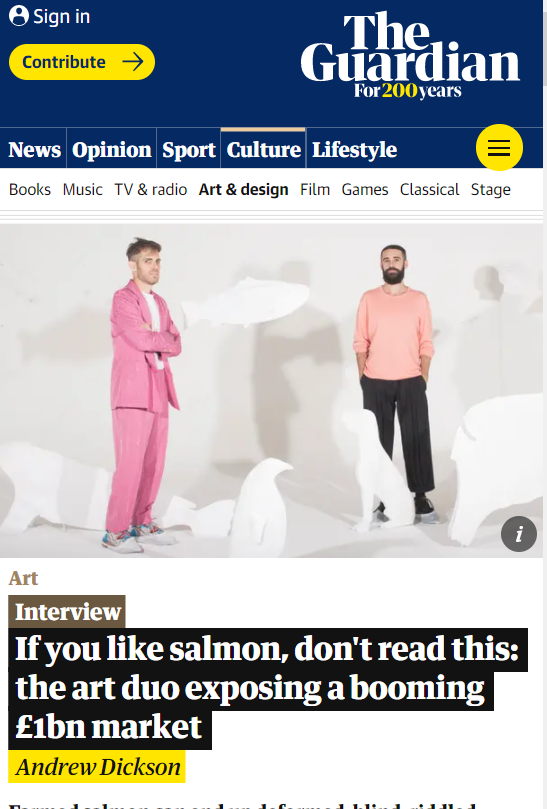

Svona er lýsing listamannatvíeykisins Cooking Sections á því sem fer fram í sjókvíaeldisiðnaðinum sem þeir beina spjótum sínum að á sýningu í Tate Modern safninu í London.

Hvert orð er satt. Þetta er óboðleg aðferð við matvælaframleiðslu.

The Guardian fjallar um sýninguna;

A modest one-room installation, it resembled a sort of natural history diorama, plunging you into the realities of Scottish fish farming. Over 15 minutes, a bare white stage populated with static sculptures of various animals (seal, penguin, lobster, flamingo) was illuminated pink, then blood-red, while a voice solemnly explained how salmon are industrially farmed.

The facts were grim: crammed into pens for up to two years and fed processed food, many end up deformed, blind, riddled with sea lice, and are often driven to eat each other. Then there’s the pollution. According to the Scottish Environment Protection Agency, insecticides from the country’s 76 fish farms are leaching out in quantities that harm other marine life. Despite all this, Brits are guzzling farmed salmon at record rates: it’s now the most popular seafood in supermarkets, worth an estimated £1bn annually to the UK economy. “Not pleasant,” says Pascual mildly.

If all this weren’t enough to make you think again about what you’re cooking for dinner, Schwabe and Pascual discovered that industrial fish farmers use a special colour swatch called the SalmoFan to customise their product. Unable to feed on their natural diet of krill or baby lobster, farmed salmon flesh is naturally grey – but no one wants grey fish, so the animals are fed dye pellets, as if they were being ordered up from Dulux. Different global markets even prefer different pinks: redder, more tuna-y tones for Japan and east Asia, lighter ones for Europe.

But why put all this in an art gallery. Isn’t it education? Environmental activism? Pascual shrugs. “The gallery is an amplifier of ideas. We see a lot of potential in cultural spaces trailblazing, paving the way for others.”